The Singapore connection of Demis Hassabis, Google DeepMind CEO and Nobel Prize winner – !

Not many children dream of winning a Nobel Prize when they grow up, but Demis Hassabis did.

And win it, he did.

In October 2024, the British co-founder and chief executive officer of Google DeepMind received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, sharing it with his collaborator, American scientist John Jumper. The other half of the prize went to American biochemist David Baker at the University of Washington.

The Google scientists were recognised for using artificial intelligence (AI) to predict the structure of virtually all the 200 million proteins that researchers have identified.

Their AI model, AlphaFold 2, has already made an impact in fields such as drug discovery and combating plastic pollution.

“I grew up as a kid reading all the great scientists and philosophers and science fiction, and I wanted to advance human knowledge,” Dr Hassabis says.

“Winning a Nobel Prize was a dream from when I was very young – to do some work that would be worthy of that level of recognition.”

The Nobel Prize is only the latest achievement for the 48-year-old polymath.

He was a child chess prodigy before teaching himself to code. At 17, he helped to create a video game that sold millions.

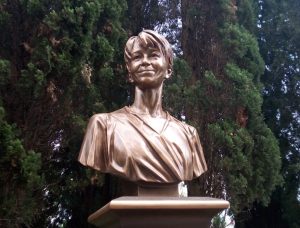

Besides being a Nobel Prize winner, Dr Demis Hassabis was also a child chess prodigy and helped create a video game that sold millions. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

After graduating with top honours in computer science from the University of Cambridge, he got a PhD in cognitive neuroscience from University College London.

In 2010, he and two others founded DeepMind, an AI start-up, in London. DeepMind was acquired by Google in 2014 for a reported US$500 million.

DeepMind’s early work included AlphaGo, a computer program trained to play the notoriously difficult game of Go. In 2016, AlphaGo made headlines for beating top Go player Lee Sedol from South Korea.

Dr Hassabis and his team then worked on protein structures, leading to AlphaFold 2.

In 2023, Google’s parent company, Alphabet, merged DeepMind with Google’s Brain division to form Google DeepMind.

As CEO of the London-based flagship research lab, Dr Hassabis leads the development of AI systems that will power Google’s next-generation products and services.

He was in Singapore in November 2024 for the Fide World Chess Championship, which was held in the Republic for the first time.

“Given that I was already travelling in Asia at this time for work, I thought I’d come to Singapore for a few days,” says the still-avid chess player.

ST chief columnist Sumiko Tan and Dr Demis Hassabis at the Capitol Kempinski Hotel on Nov 23, 2024.ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

I’m meeting him at the Capitol Kempinski Hotel in Stamford Road where the Google team has booked a room for his meetings. Because he is likely to talk about chess, the team has helpfully brought along a chess set as a prop for the photo shoot.

His schedule is packed and lunch is impossible, I’m told. I have a 30-minute slot at 4pm.

Dr Hassabis arrives carrying a paper cup of coffee. He’s in the Big Tech CEO get-up of dark T-shirt, trousers and jacket.

He has an amiable, unassuming manner and when he smiles – which he does often – his boyish face lights up and his eyes twinkle behind blue-framed spectacles.

As we settle into our chairs, he glances at the chess set and nods, approvingly. The pieces have been arranged correctly.

There’s no time even for a small bite, so we settle for water from the hotel room.

Dr Hassabis is no stranger to Singapore.

His 77-year-old mother, Angela, was born here. She went to Britain in the early 1970s to train as a nurse to special needs children and is now a naturalised Briton. His father, Costas, 78, is Greek Cypriot.

“I have a lot of fond memories of Singapore when I was young,” Dr Hassabis says, adding that he had met a cousin earlier that day and was meeting more Singapore relatives later.

His mother, who was raised by her grandmother, often visited the older woman in Singapore. Up till when he was about 10, when his great-grandmother died, the young and precocious Dr Hassabis would visit Singapore every summer for two- to three-month stretches.

His mother often visited her grandmother in Singapore, and up till he was about 10 years old, the young Dr Hassabis would visit Singapore every summer.PHOTO: COURTESY OF DEMIS HASSABIS

He later sends me photos of his holidays in Singapore, including swimming at Changi Beach and with his Singapore relatives.

I wonder if he knows any Chinese dialect. He says his mother speaks Cantonese, which he understands a little. “Whenever she’s with her Singaporean friends, she speaks a kind of Singaporean English,” he adds with a smile.

She doesn’t like travelling these days so hasn’t been back in Singapore for a few years. “She sends me instead to say hi to all the family, and then we video call back home to her.”

Were your Singapore cousins excited by your Nobel win, I ask.

“When I’m with family, I like to just be normal, so we don’t really talk about it very much,” he says. “But they’re proud, of course.”

Follow your passion

While he is recognised as one of the smartest thinkers in his field, Dr Hassabis wears this lightly, coming across instead as down-to-earth and approachable.

I mention that I’d read he celebrated his Nobel Prize win with a poker game joined by friends including world chess champion Magnus Carlsen.

He laughs. “Yes, it was the next day actually, totally independent of the Nobel.”

One of his good friends had organised a poker/chess evening with some of the best poker and chess players who were in London for a tournament. The night turned into a celebration of his Nobel win. “It was very fun.”

The scientist, who has two sons with his molecular biologist wife, was born in 1976, the eldest of three children, and grew up in north London. His brother is a professional poker player and his sister a composer and pianist.

The family remains close-knit and they all live near one another in north London.

His parents were quite bohemian and creative, he says. His father did many jobs, including as a singer-songwriter. “He wanted to be like Bob Dylan, I think, and even now in his retirement, he’s writing an opera, so that kind of gives you an indication of what he’s like,” he says fondly.

His mother worked for a time as a manager at the John Lewis department store. His parents also ran a toy shop and later became teachers.

“I used to get the toys or games that had missing pieces and I used to create new games out of them for my brother, sister and me to play. I think that encouraged my creativity.”

His parents urged the children to chase their passions. “Go deep with them and don’t worry about being unconventional and, you know, eventually things will work out,” he describes their approach.

“My career has been, obviously, very unconventional and I was very encouraged by my parents.”

Dr Hassabis’ parents (left) with him as toddler, and relatives in Singapore.PHOTO: COURTESY OF DEMIS HASSABIS

Chess, which he learnt at four, was a large part of his childhood and he was at one point the No. 2 player in the world in the under-14 category.

He was homeschooled for a couple of years because he was travelling so much to take part in chess tournaments. It wasn’t easy, as he played mostly against adults, and travelling was costly.

“My parents were both immigrants and we grew up in quite a poor area of London,” he says. “There was always a lot of pressure to make sure, if you’re travelling to tournaments, you did well, because it was expensive, and we didn’t have much money.”

But, he says, “dealing with pressure when you’re young makes you stronger for later”.

I wonder if his parents pushed him in chess.

“No, not really,” he muses. “It was mostly myself. I think I’m a very driven person. I don’t know where that came from. My brother and sister, they’re very different. I always really enjoyed improving and mastering things and getting better at things and learning things. I love learning. Still love learning.”

He’s a big advocate of children learning chess at school as the game trains the mind. “Because I started playing chess when I was four, it really was very formative in how I think.”

Chess, which Dr Demis Hassabis learnt at four, was a large and formative part of his childhood.PHOTO: COURTESY OF DEMIS HASSABIS

He wanted to be a professional chess player, but when he was 12, decided that “maybe it’s too narrow a thing to spend your whole life on”.

By then, he had discovered another passion – computers and programming. He got his first computer when he was eight with his winnings from chess tournaments. It was a British-made ZX Spectrum, which was popular in Britain in the 1980s. He taught himself programming from books.

It was not an area his parents were versed in. “They’re not interested in technology, so I don’t know where I got that from, but I’ve always loved computers.”

He completed his A levels at 16 but was too young then to enter Cambridge University. The avid gamer decided to build video games in the meantime.

He joined the computer game company Bullfrog Productions and was, among other things, lead programmer for Theme Park, which simulated the experience of creating an amusement park. It was very successful and earned him enough to fund his expenses at Cambridge.

He continued with game development after graduation and was also active in games competitions. He won the Pentamind World Championship, a mental sports event, five times.

“It was always self-driven,” he says when I remark that he’s an over-achiever. “I was doing it for my own satisfaction, really, and to try and see how far I could push things, and what could be achieved.”

Fascinated by the workings of the brain, he went back to academia and in 2009 completed a PhD in cognitive neuroscience at University College London (UCL) investigating memory and imagination processes.

Dr Demis Hassabis with his parents, Costas and Angela Hassabis. He has a younger brother and sister and he says they all live near each other in north London. PHOTO: COURTESY OF DEMIS HASSABIS

He founded DeepMind in 2010 with Shane Legg, whom he had met at UCL, and Mustafa Suleyman, a friend of his brother’s. Dr Legg is now chief AGI (artificial general intelligence) scientist at Google DeepMind and Mr Suleyman is CEO of AI at rival Microsoft.

DeepMind started with an interdisciplinary approach to building general AI systems. An early breakthrough was a program which learnt to play 49 different Atari games from scratch just by observing the raw pixels on the screen and being told to maximise the score.

Early investors in DeepMind included entrepreneurs Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

DeepMind was little known to the public until the AlphaGo match against Lee in 2016, when the machine won four out of five games.

Go, which Dr Hassabis played at Cambridge, was always considered the “Mount Everest” of games AI, he says.

Beating a world champion was “the big watershed moment” not just for DeepMind but AI in general. “When we won 4-1, that was a big moment that sort of, really, was the beginning of the modern AI era that we see today.”

When the DeepMind team returned to London from Seoul, it started work on protein structures.

“The reason to build AI was not to play games,” Dr Hassabis says. “That was just the means to an end, which was to apply these algorithms to real world problems, really important ones in medicine, in science and in industry.”

Games were used to train algorithms and develop algorithmic ideas because they have a very clear objective – you need to win the game or maximise the score – so it’s very easy to see if you’re making good progress, he explains.

AlphaGo inspired a new era of AI systems that have solved issues ranging from video compression to advancing weather predictions. Then, of course, there is AlphaFold.

Google does not charge for the use of AlphaFold’s predictions and has made them freely available through a number of tools. Over a third of AlphaFold users are in the Asia-Pacific, including in Singapore, where it is being used in areas such as Parkinson’s disease research.

With such rapid advances, should AI be feared, I ask.

Dr Hassabis says there are many unknowns, but having spent nearly 30 years working on it, he believes AI to be “the most beneficial technology ever”.

“I think we’ll be able to use it to cure diseases, find new energy sources. So many of humanity’s greatest challenges that we face today AI can help with, from climate to health,” he says.

There are risks with any new transformative technology, so governments, civil society, academia and industry need to discuss what AI should be deployed for and mitigate the bad uses, he adds.

Does he have advice for someone keen to enter the AI world?

He believes the next big advances would come from being an expert in at least two areas and doing interdisciplinary research between them. “I would recommend embracing AI and applying it to some other area that you’re an expert in, and see how AI can transform it. I think that’s going to be the next big business area.”

I squeeze in a last question.

Having achieved so much, how does he see himself and what does he write under occupation in an immigration form?

“I never know what to write down on those things,” he laughs. “I think of myself as a scientist, first and foremost, and then an entrepreneur, engineer and then manager, I guess.”

To that, he can now proudly add Nobel Prize winner.

Join ST’s WhatsApp Channel and get the latest news and must-reads.

КОММЕНТЫ